From an invited talk in a Mentoring Session for the Language and Social Processes SIG of AERA (April, 2024)

I’d like to use this opportunity to offer a tribute to my father, Charles Nicholas Faulstich – who never saw me give an academic talk, partly because when he was alive, I was a junior scholar, and I was too scared to invite him to any academic gathering; I didn’t know how to bridge my home and work worlds. (Those of you who have read anything I’ve written in recent years will know I have changed my approach on that a lot, and I believe that it’s important for all of us to draw on all of who we are – our accumulated understandings of the world as shaped by our social positions and life experiences – and to integrate that into our work – more than just writing positionality statements in a stand-alone way.)

I know my father would have been very proud to see me in my professional persona, and I regret that I never gave him that opportunity, out of my own insecurities.

To honor my father, I will draw on his words in this talk, using them to reflect from my current vantage point as a senior scholar on how we “elders” can help younger folks to make their way in this business. I hope this will be helpful to you as you forge your pathways in academia – and in life.

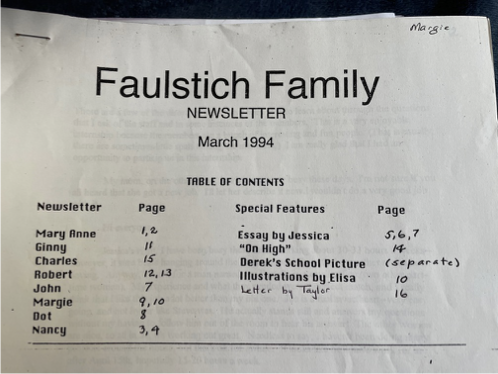

In the later years of my father’s life, he wrote a few columns for his church newsletter, and also for a family newsletter that my mother instituted in an attempt to keep my large family – eight children, and their own growing families, scattered around the country/world – connected. She solicited news entries from each of us a few times a year, cut and pasted them (by hand) into a document, and snail mailed them out to all of us.

As a scholar of language and literacy, I have wondered about analyzing the fat folder of newsletters I gathered over the course of more than two decades. I’m sure they would provide a fascinating look into how we represented and narrated our lives, and illuminate an interesting family literacy practice from before the time that we had Facebook and other forms of social media to connect us.

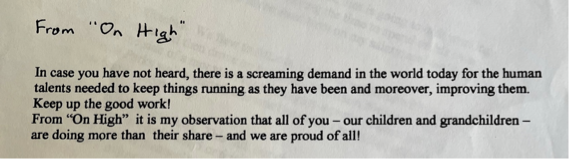

What I did do, when my father died, was take a close look at his words, in the brief snippets he wrote called “Notes from on high.” By this, he meant his views from an advanced age, as well as his position as “patriarch” (a word that made my feminist self bristle).

Initially, I found my father’s words obtuse, pompous, and confusing. He sounded like he was trying too hard to appear erudite. For example:

As graduate degrees continue to accumulate…your aging patriarch continues to be humbled. How can one, who can claim no formal education other than “MIT after dark,” be involved in such a proliferation of wall decorations? Perhaps he should ameliorate his feelings by considering that this all became possible and yet the expenditure of time needed to obtain a degree was not required on his part.

My father is referring here to the fact that he didn’t get to go to college, though he did take a few night school classes through MIT, perhaps through the GI Bill. He was the oldest of six siblings and his father died when he was 12, so he gave up his dreams of higher education and went to work to support his family. He passed on his dreams to his eight children, and indeed he was very proud of all the “wall decorations” we accumulated.

When I think about my father’s life trajectory, I’m more sympathetic to his over-striving voice. His is a voice I hear in many young scholars and that I imagine I used myself earlier in my life, when I was trying extra hard to sound “smart,” and struggling with imposter syndrome.

It took me a long time to learn to write in more straight-forward ways. It took growing in confidence about my own ideas, and clarity in my own thinking, so I didn’t need to hide behind words. I think here of Bill Labov’s work, for example his study of two African American male speakers – one who was college-educated, and one who was not. Labov’s analysis shows the clarity of the working-class speaker’s ideas, and the convolution and tautological thinking of the middle-class speaker’s words. They sound quite impressive, but they avoid taking a clear stance (as many intellectuals do).

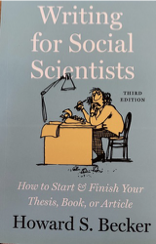

Howard Becker’s book, Writing for Social Scientists, helped me a great deal. I recommend it to all my students, and to you. In a chapter on Persona and Voice, Becker describes a graduate student who believed that “classy writing” involved using “big words” and syntax that was supposed to be difficult for untrained people to understand. He quotes this student as saying:

When I read something and I don’t immediately know what it means, I always give the author the benefit of the doubt. I assume this is a smart person and the problem with my not understanding the ideas is that I’m not smart. I don’t assume that either the emperor has no clothes or that the author is not clear because of their own confusion about what they have to say.

How many of us have felt that way?

I recognize, of course, that racism and sexism as well as classism enter in to judgements about how erudite one is, so there is more pressure on women and people of color to “sound smart.” But at what cost to the take-up of our ideas?

In 2017, three scholars wrote 20 fake papers “using fashionable jargon to argue for ridiculous conclusions” (The Atlantic, October 2018). Seven were accepted for publication in peer-reviewed journals. The three authors were inspired by an earlier hoax by Alan Sokal, a physics professor, whose bogus article, “Transgressing the Boundaries: Towards a Transformative Hermeneutics of Quantum Gravity,” was published in the cultural studies journal, Social Text.

Did the editors of this journal assume that the authors must be saying something important, without really following the arguments (which were completely hollow)?

I do not want to fan the flames of attacks on critical and identity-based scholarship, as these scholars arguably did. But I do want to suggest that it is possible to convey complex ideas in more comprehensible prose, and I see it as an ethical imperative to do so, if we want our ideas to be useful in the world, not just to construct a scholarly persona. I now incorporate into my graduate classes the expectation that students provide a “translation” of their academic papers for a general audience: for their grandmother, their neighbor, a teacher, a friend.

As convoluted as some of my father’s prose was – sometimes seemingly in purposeful and even clever ways, as in the first excerpt – there were many kernels of wisdom in it. I want to translate a few of his thoughts and apply it to our work in academia.

My father recognized that our views of the world change over time:

To be honest with ourselves we must admit that many things viewed from our present situation in life are not the same as we saw them earlier in life.

How many of you who are now professors already see graduate school differently than you did when you were a student? Our ideas may change as we cross into new identities, take up new social positions, gather new experiences, acquire more life wisdom…or as the world around us changes. It’s OK for ideas to change – not just to evolve, but sometimes to radically transform. This can demand being willing to let go of some ideas that we have gotten attached to. Recognizing that we don’t even see the world in the same ways as we did when we were younger may help us to grasp why other people do not see things in the same ways now.

At the same time, we might remind ourselves that our changing social positions surely shape what and how we see, as feminist Standpoint Theory would suggests. As we acquire more privilege, we may not see our own relative power in the social world.

Academia looks very different to me now than it did when I was starting out, and I would likely do some things differently if I had my current understanding then. Especially, I think I would give the business less power over me. I would strive to notice where my own anxieties and insecurities arose, and more consciously choose how I want to be in this business.

My father’s words again:

As a struggling young person, I seemed to be most aware of my inadequacies and little aware of my strengths. My present view is that the inadequacies of people must be tolerated because people are all we have to keep things going…So never let feelings of inadequacy stand in the way of giving your all for the good of mankind.

My father valued education for his children, and was keenly aware that he was the only one in our large multi-generational brood without a college degree. At the same time, he reminded us, as I will remind you:

Formal education without the application of common sense…cannot alone meet the demands of the times.

And what are the demands of the times? What role should scholars play in the face of social and ecological crises? Where should we put our time and energy? As language scholars, how can we leverage our expertise to address critical issues of the day? Will our work contribute to the making of a better world? Does it meet what I like to call the “so what?” test – or my father’s test of “common sense?”

As we confront the challenges of the future, let us not forget where we have come from. My father valued our ancestors:

Who are those people figuratively standing behind you who mean so much to you but whom you’ll never know? Would not any one of us give our eye teeth to know these people and offer them a gift? And yet we would merely be returning what we had previously received from them, ourselves…

For academics, we might honor our ancestors of personal lineage – those people who fed, clothed, and supported you in myriad ways that helped you to get to where you are now. We might also recognize our metaphorical ancestors: those scholars upon whose ideas we build. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t sometimes challenge their ideas – reinvent and re-imagine them – but can we do that in ways that offer them a gift?

My father certainly knew that the world changes continuously, and we can’t hang on to the past.

These are people from another world yet we are from their world. Are we not reincarnations of their wildest dreams, considering what little they could have known about our lifestyles? The world today is not a place they would recognize, nor could they cope on equal terms with what we accept as everyday events.

The same is true for the academic world that you, and your students, will be living in the years to come. The advent of AI alone assures that we cannot really imagine what academia will be like in twenty, fifty, or even just a few years. AI introduces huge new questions for researchers of language and social processes. For example, how can/should we – and our students – use this tool to facilitate our writing? Early evidence suggests that many people are using it to break through writers’ blocks – to get something started that they can then work with. There may well be merit in this. But does it undermine the value of struggling through those messy first drafts ourselves – the process of getting clearer on our own thinking?

I’ll close with these words from my father:

In case you have not heard, there is a screaming demand in the world today for the human talents needed to keep things running as they have been and moreover, improving them. Keep up the good work!

In my large family, a great deal of attention went to fairness. We were all expected to take just our share of family resources, and to give our share for the collective good. In that same spirit I would like to encourage you to do your share to improve the world.

From my vantage point – and I’m sure my father would agree – I can say that the years go really fast. I hope you won’t waste your time and energy being swallowed up by fears and anxieties. I hope you will find joy in your work, and imbue it with purpose and meaning, so you can look back someday from “on high,” and know that you led a life well lived, and that you contributed your share to making the world a better place.