I was recently awarded the John J. Gumperz Lifetime Achievement Award from the Language and Social Processes SIG of the American Educational Research Association (AERA). I am sharing here the acceptance speech I gave, reflecting on my own journey in the field of language and social processes, and imagining the future.

The words “honored and humbled” feel a bit hackneyed these days, but I can’t think of better ones to use as I accept the tremendous honor of being awarded the John J. Gumperz Lifetime Achievement Award from the Language and Social Processes SIG. Many thanks to the awards committee and to the outgoing chair of this SIG, Diana Arya, for all your work. And thanks for to all for taking the time to listen – or read – these words. I know we are all bombarded with all kinds of words these days, so your time is a gift.

Life is lived going forward, but only understood looking back, to paraphrase Soren Kierkegaard. From this vantage point, I can see how the paths that John J. Gumperz and others forged made possible what I have been able to know, do, and contribute to the world. There are too many to name or include on this slide, but I’d like to recognize a few more of the people whose work inspired mine, both directly and indirectly, across the years.

In the top row, my nominator and letter writers who also work in Gumperz’ tradition of the Ethnography of Education – giants on whose shoulders I stand: Judith Green, Fred Erickson, Cynthia Lewis, Carol Lee.

I’d like to thank Judith Green, not just for surprising me with this nomination, but for supporting my work since the start of my career. I recall driving up to Santa Barbara to meet with her about a manuscript I had submitted to Reading Research Quarterly based on my dissertation work. She was incredibly generous of her time and guided me in what became my first major publication, which centered on how gender constructed literacy, and literacy gender, through texts, talk and their take-up in two bilingual classrooms (Orellana, 1995). I’ve been trying to pay forward the mentoring she gave to me – a total stranger to her at the time – ever since.

Next, my graduate and postgraduate advisors and mentors: Robert Rueda, Nelly Stromquist, Barrie Thorne. I keep trying to pay their mentorship forward as well! Here I’d like to give a shout-out to a forthcoming book that honors the work of Barrie Thorne (Gender Replay: On Kids, Schools and Feminism); I have a chapter in it in which I credit her with much of what I learned about ethnography, especially in terms of working with love and respect for children, and finding joy in the work.

And then, more thinkers and doers who have influenced my work in small and large ways. I wonder how many you recognize?

You might note that this is a bit of an eclectic group: from diverse disciplines, pursuing different areas of inquiry, in different contexts, with different populations, both in and out of school. I have long taken great pleasure in traversing boundaries in the pursuit of interesting ideas, finding the conceptual frameworks that are best suited to the task at hand, and merging their insights for particular analytical tasks. I also strive to conjoin different perspectives that point to similar things, bringing those frameworks together rather than marking their distinctions, in the silo-ed approach that academia tends to reinforce and reward. In my own work, I’ve cited all of these people, and many more (apologies to all that I’ve left out), and also…The Little Prince, Dr. Seuss, Thich Naht Hahn…my children, my students, my large extended family, my friends, the young people with whom I’ve worked over the years, as well as many more-than-human beings and beautiful places and spaces on this planet.

All of these beings have been my teachers and have shaped who I am, what I think about, and how I move in the world, as I strive to be a compassionate, equity-minded, reflective social justice innovator — continuously trying to forge “the next best version of myself” – while acknowledging, even embracing, my own imperfections. (Accepting my own helps me to allow room for others’ as well.)

With many conceptual meanderings, a central through-line in my work has been methodological, working in the tradition that John Gumperz established: the Ethnography of Communication. This approach to combining ethnographic observations of social and cultural processes with close analyses of discourse was foundational for my research on immigrant child language brokering (Orellana, 2009).

When I set out to study language brokering my intention was to understand the practice in all its complexity, and to map the range and nature of children’s experiences as brokers. To this day, it frustrates me a bit that researchers seem to focus on the questions that most perplexes them: (1) Is this good, or bad, for children? And (2) “How do children feel about language brokering?” And most often, these questions were asked of adults looking back on their experiences, not children themselves.

At the time that I began my research, some 25 years ago, and even to this day, remarkably little research has considered the social and cultural processes that both shape and are shaped by this multidimensional practice; very little research on language brokering has been based on direct observation of actual brokering encounters. (There are a few important exceptions, such as the work of my colleague Inmaculada García-Sánchez, who has also worked in the tradition of the Ethnography of Communication to study this practice with Morroccan immigrants in Spain.) Using ethnographic methods and discourse analysis within an Ethnography of Communication framework, I was able to show what children do in language brokering, how they do so, and how it matters for their communities as well as for their own learning and development.

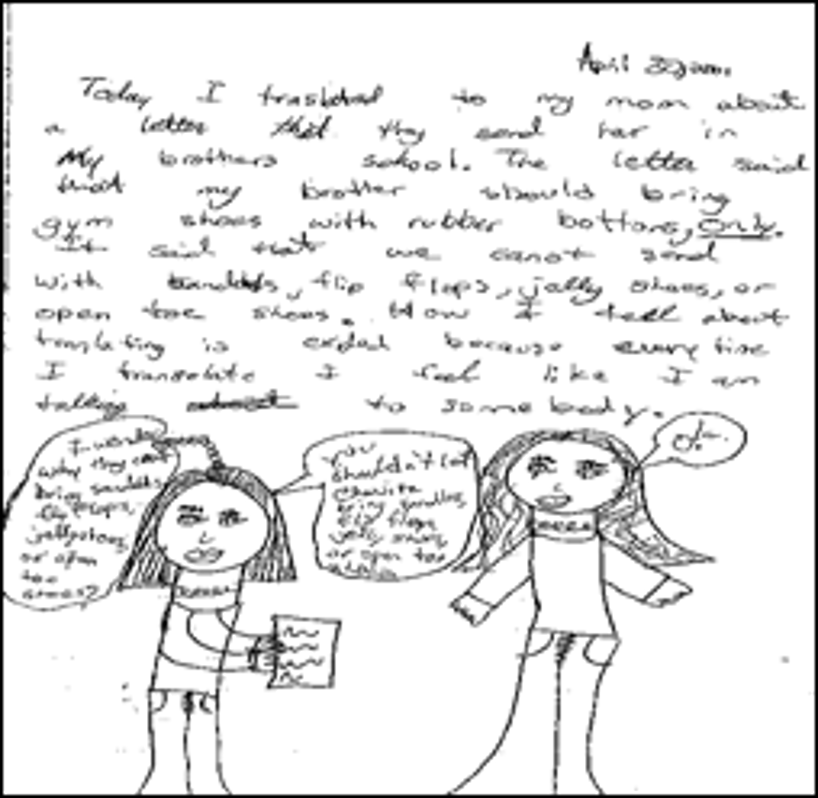

Ethnographic work with many child language brokers taught me that children feel MANY things, because language brokering is not a single thing: it is shaped by the contexts, the demands of the tasks and texts, the nature of the relationships in which they are set, the supports and constraints of the interactions. The Ethnography of Communication helps us to see these complexities. Combining this with sociohistorical perspectives on learning in different time scales, we can think about the cumulative effect of children’s experiences with a wide range of language brokering tasks, over time. This is much more productive than trying to prove the positive or negative effects of the practice, or to answer find a singular answer to how children feel about doing the work. But from an Ethnography of Communications perspective, I think it’s worth quoting 10-year-old María here, who wrote in this diary entry that how she feels about translating is “excited” b/c it feels like she’s talking to somebody. And indeed, she IS talking to and with her mother, as she reads a text sent home from her brother’s school. And she shows herself talking to her mother, as well as thinking critically about school practices.

Even as I aimed to unpack the complexities and nuances of this multi-dimensional practice through an Ethnography of Communications framework, collecting a wide range of data including recordings of actual language brokering encounters, and children’s reports on them in diaries like María – my aim was never just to understand the practice as an interactional phenomenon, but to draw implications for teaching and learning, in and out of schools. I began focused attention to making connections between children’s everyday language experiences and the things that schools value and prioritize by taking up Carol Lee’s approach to Cultural Modeling: working with others to design pedagogical approaches that leverage, level, sustain and expand the everyday linguistic competencies of students from non-dominant cultural groups.

I also helped to design new learning environments in informal learning spaces. Here, I’d like to give a shout out to UC Links’ model for sustained, engaged university-community partnerships, the legacy of work established by Mike Cole and Olga Vasquez in the 1980s, and that I inherited from Kris Gutierrez at UCLA, where I directed an after-school program called “Bruin Club” for 11 years. Bruin Club became a space for playing with language, and for learning with and alongside kids while we experimented with designing learning spaces and studying them using the tools of the Ethnography of Communication.

This focus on language processes in contexts of linguistic and cultural diversity has been a through-line of my work. As I shared in the LSP newsletter, it wasn’t necessarily a logical place for me to land, given that I was raised in a rather homogeneously white, working class, Catholic, English-speaking town. But the ethnographic study of communicative practices helped me to understand the world beyond the one I was raised in. It helped me to expand my ways of seeing – and hearing – and to see the beauty and power of language in interaction in bi-, multi- or translingual settings (i.e. the most places in the world). It can help all of us to expand our own ways of knowing, doing, thinking and being. We can use its tools to appreciate both commonalties and differences in the human experience, to listen across and sometimes mediate between divergent perspectives, as child language brokers do every day.

This is the work that I think is most needed for the future, as I call for in my latest, arguably my boldest, book. I think most of us know that the world is increasingly polarized and see the problems in that. But do we see the problems of perpetuating polarizations within our own fields, our own spaces, our own practices, our own minds? If we look around, divisions and polarizations abound even among relatively like-minded people in academia. Getting beyond them – finding connections and commonalties more than marking what divides us – perhaps using the tools of the ethnography of communication and a mindful (heart-centered, compassionate) approach to ethnography (conjoining mind, heart, and activity in our commitments to profoundly transforming the world) – is, I think, the greatest challenge of our times.

One concept that has been the subject of some level of polarization in the field of language and social processes, centers around translanguaging, and more generally what has been called the “trans” turn in the social sciences, encapsulated in a proliferation of (relatively) new linguistic terms, including translanguaging, transculturality, transracial, transraciolinguistics, transgender, translocal, transmodalities, transcultural repositioning…. In all of these words, the prefix “trans” suggests movement, fluidity, and change. It calls us into transgressive, transitional and transcendent spaces, inviting us to cross over borders and move through walls that have been erected by humans and reinforced by social institutions. The tensions lie with those who want to keep things more fixed, solid, demarcated, everything in its place

As someone who delights in boundary crossing, I’m thrilled to see and participate in these transgressive and transformational ideas. In terms of translanguaging, I’m happy to tear down some of the walls that got erected between languages in the rise of the modern nation state, and to challenge schools’ roles in reinforcing lines between somewhat (though not completely) arbitrary linguistic forms. I also appreciate the focus on the user’s perspective rather than the institutional ones, as Ofelia García has helped to differentiate.

At the same time, I know that walls can be protective. Seedlings get nurtured in small enclosures to ensure their growth. Sometimes we need to disentangle roots that get matted and clumped together, for the health of individual plants. Putting up some protective walls may be especially important for languages that are at threat for extinction and erasure.

I have mostly steered clear of the specifics of the debates between supporters and critics of translanguaging, instead bringing my “middle child” viewpoint, brokering stance, and what I like to think of as a decolonizing orientation, to see the issues in what Patricia Hill Collins long ago taught me to think of in “both/and” terms. I see both the power of the concept of translanguaging, and the challenges it presents, both conceptual and practical. I see the importance of naming languages that have been invisibilized, erased, or murdered, not letting them get lost in a dizzy celebration of hybriditiy. At the same time, I see the creative genius of young people as they mix and remix heritage language forms and emergent ones in exciting, surprising, innovative, transgressive and transformative ways ways – and I look forward to more work that documents and analyzes that creativity, and what it is used to do in the world.

Sociohistorical activity theory has taught me to see all binaries as generative tensions. The resolution of these dialectical tensions involves not getting caught in them, not reinforcing the polarizations that can pull us apart – but transcending, moving beyond, looking for what may emerge. Looking for possibility.

I would suggest that moving beyond the binaries that divide us involves attention to language, but not only to language, or at least not just to words. As Gumperz showed us, we need to see language as intricately bound up in social processes. We need to think about critical social processes of the times we are living: a time of increasing social and political destabilization and potential ecological collapse. We need to listen to what is said, and also what is not said: hearing silences, as Ariana Figueroa Mangual and Claudia Cervantes are doing in their work. We need to hear not just what people say, but what they understand of what others say, as Adrienne Lo and Christhian Fallas Escobar and others are showing as they examine the complexities of the listening subject. And we must listen not just with our heads, and our ears, but with our hearts, as I have been calling for, for some time. We need to listen both over and under the words that others use, with interest and curiosity, like good ethnographers, seeking to understand from emic perspectives.

Gumperz was perhaps ahead of his time in bringing appreciation for linguistic and cultural diversity into Academia. I’d like to think that my work has helped to widen that space a bit more, making room for the next generation of scholars to do so in bigger and bolder ways. I’d like to end by naming the students I have mentored across the years. (These are just the ones I have most closely mentored – students whose committees I chaired and a few “honororary mentees” as well.) I think you’ll recognize many their names and see how the legacy of John Gumperz has extended across the years (and across the world!).

Seeing the work that is being done by my students, and theirs – and imagining the work by others who are growing up today in places where linguistic diversity is the norm – assures me that the future of research in the Ethnography of Communication is in very good hands. I can only imagine – with wonder and awe – what young scholars of today will be able to do as they carry these legacies forward, honoring those histories, but also mixing, re-mixing, riffing and innovating as they forge new ones of their own.