I haven’t written in this blog for almost a year.

I haven’t known what to say, so I’ve mostly been listening.

What words can I possibly offer to the world that will make any kind of difference in the state of affairs in which we find ourselves, as a nation and a world: the resurgence of overt forms of white nationalism, xenophobia, misogyny, racism, hatred and vitriol; violent expressions of rage and social unraveling such as was evident in the Las Vegas terrorist rampage; regressive policies that undo gains made over the last eight (or fifty or more) years on the social, civic, environmental and other fronts; massive destructive impacts of climate change on vulnerable populations all around the world (Puerto Rico, the Caribbean, India, Bangladesh, West Africa); the renewed threat of nuclear war; growing social divisions of all kinds; and more?

How can I speak about the things I believe in, and want to build up: love, kindness, compassion, empathy, transcultural understanding, joy and play – without denying or ignoring the tremendous pain that reverberates around the world?

But I’m convinced that where our attention goes, energy flows, and what we resist or fight against directly, we make stronger. When we find openings and build on them we make stronger the things we want to see grow.

So I’m back to talking about LOVE in relation to education.  I make a public plea in defense of love and education here: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/in-defense-of-love-and-education_us_59f2489be4b05f0ade1b55ea

I make a public plea in defense of love and education here: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/in-defense-of-love-and-education_us_59f2489be4b05f0ade1b55ea

In this blog, I’ll give a little more depth to these ideas. But they are still very much thoughts-in-progress. I welcome dialogue. As Paolo Freire (1970) wrote: “Love is at the same time the foundation of dialogue and dialogue itself.”

Defining Love

How to define something that humans seem to understand in a way that surpasses words? I’m reminded of an image of graffiti on a New York subway wall: Love is Love.

In my writing about love to date – e.g., in my (2016) book, Immigrant Children in Transcultural Spaces: Language, Learning and Love – I have resisted extensive complexification of this phenomenon that is so fundamental to the human experience, and yet so elusive. I rather loosely defined love as a force that helps connect us with others and with the larger world; as a quality of being and moving in the world; as a stance that allows us to see potential more than obstacles; and a force that animates learning, from within. My aim was to show how, in the after school program that is the center of my praxis in Los Angeles, we use love for words, the world, and the people we are learning with and from as “animators” of learning, and to consider how participants respond and engage in this space.

But perhaps I can do a bit more here, and better connect with the ideas of others – the many philosophers, poets, theologians, musicians, revolutionaries, and social scientists of different stripes who have given homage to love. I will attempt to bring some of these ideas together, with a focus on love in relation to education and social transformation. Readers can decide just how helpful it is to try to pin love down in words; I’m certain I will not succeed in “getting the words just right,” and that there will be both more and less that could usefully be said. I hope readers will add to the conversation if you are moved to do so.

Love can be considered a fundamental human drive for connection to others (Maslow, 1970) and to the world (Freire, 1978), and an interactional disposition that can help us transcend barriers between the self and other (Badiou, 2017). It can be a force that helps calm the “monster” that the egoic drive to be “right” creates (echoes of Francisco Goya’s “el sueño de la razón crea monstrúos”),  and one that helps us get in touch with our feelings and spirits more than our minds, seeking “positivity resonance” (which Frederickson, 2013:10, defines as “micro-moment(s) of warmth and connection that you share with another living being”) over opposition.

and one that helps us get in touch with our feelings and spirits more than our minds, seeking “positivity resonance” (which Frederickson, 2013:10, defines as “micro-moment(s) of warmth and connection that you share with another living being”) over opposition.

Revolutionaries and critical social scientists have considered love as a driving force for social change. Love serves to re-humanize oppressed peoples whose humanity has been stripped from them by the larger society, and awaken critical consciousness. For Paolo Freire (1970) love was “an act of freedom” that should be used to propel other acts of freedom; it is “at the same time the foundation of dialogue and dialogue itself.” Chela Sandoval (2014) builds on the ideas of Freire as well as Che Gevara, Franz Fanon, Emma Pérez, Trinh Minh-ha, Cherrie Morega to posit love as a hermeneutic, a “decolonizing movida” to propel social change. Adopting loving orientations toward ourselves and others as a revolutionary practice helps us to seek out potential goodness and create hope.

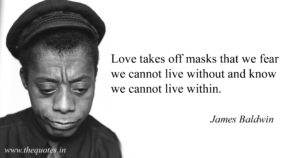

While most working from a left, progressive, “critical,” or revolutionary tradition have focused on love for and within oppressed populations, Sandoval (2014) suggests that love can help “transit all citizen-subjects, regardless of social class, toward a differential mode of consciousness.” James Baldwin (1963), as well, saw love as humanizing force for all people, including for oppressors who project their own unresolved pain onto the oppressed.

While most working from a left, progressive, “critical,” or revolutionary tradition have focused on love for and within oppressed populations, Sandoval (2014) suggests that love can help “transit all citizen-subjects, regardless of social class, toward a differential mode of consciousness.” James Baldwin (1963), as well, saw love as humanizing force for all people, including for oppressors who project their own unresolved pain onto the oppressed.  Baldwin saw the opposite of love – hatred – as a force that does not just dehumanize the object of hatred, but that destroys as well the one who hates.

Baldwin saw the opposite of love – hatred – as a force that does not just dehumanize the object of hatred, but that destroys as well the one who hates.

Transcending the Cartesian divide

One of my main aims in talking about “love” has been to challenge the Cartesian divide: the distinction between mind and body, spirit and intellect that was reinforced and developed in the European Enlightenment and the rise of what we know as Modernity. This is also a split that severs the body from culture and that privileges the masculine, narcissistic subject (Irigaray, 1996) (which is key to why love is seen as “soft” in the masculinist worlds of academia and politics). I am following a long line of philosophers and scholars who have called for a transcendence of dualistic thinking and reintegration of intuitive or non-rational dimensions of human understanding with the rational, linear, logocentric mind processes that assumed ascendency in the last few hundred years, as I detail briefly (without the depth t hese ideas deserve) here. This is not a call to abandon “scientific” (or masculinist, rational, mind-driven) ways of knowing, but to re-balance binaries that have gone awry.

Within the social sciences, theorists working loosely with these kinds of challenges to modernist rationalism include Gloria Anzaldúa (2009), Dolores Delgado Bernal (2006), Antonia Darder 2017), Norma González (2006), Laura Rendón 2014), Abhik Roy (2015), Chela Sandoval (2014), and of course Paolo Freire (1993). (Please contact me if you’d like a list of references.) I’m sure there are others, and again I hope readers will add to this list. In different ways, each of these scholars reminds us to attend to aesthetic and affective dimensions of learning and living, not just instrumental, structural, intellectual or cognitive concerns, and to transcend forces that divide humans from themselves, from others, and from the world. Norma González, for example, underscored the intimate (if fractured) connection between language, emotion and identity for Latinos in the U.S. in her beautiful ethnography, I Am My Language: Discourses of Women and Children in the Borderlands.. Laura Rendón builds on Eduardo Galeano’s idea of “sentipensante” – the marriage of thought and feeling – as a foundation for pedagogy, learning and teaching in her book, Sentipensante Pedagogy. Sandoval (2014) writes about those aspects of human experience that “function outside of speech, outside of academic criticism” and that are not expressable in words. (Indeed, she speaks directly to the challenges I face in trying to pin love down in words here.)

I Am My Language: Discourses of Women and Children in the Borderlands.. Laura Rendón builds on Eduardo Galeano’s idea of “sentipensante” – the marriage of thought and feeling – as a foundation for pedagogy, learning and teaching in her book, Sentipensante Pedagogy. Sandoval (2014) writes about those aspects of human experience that “function outside of speech, outside of academic criticism” and that are not expressable in words. (Indeed, she speaks directly to the challenges I face in trying to pin love down in words here.)

Healing splits

Transcending the Cartesian divide involves a call to heal from the kind of psychological “splitting” that humans have done, both individually and collectively, in many different ways, across time and social contexts. Indeed, what has most propelled me to try to bring non-academic, non-rational (i.e. “spiritual,” for lack of a better word) ways of thinking into academia has been a conviction that there are limits to what we can understand and do with our rational minds, and that if we really want to effect fundamental change in the ways humans orient to the world and to each other, we need to identify ways of transcending or transforming the separating tendencies that seem to compel our species, again and again, to identify groups of “us” and “them,” creating scapegoats, and constructing dehumanized “others,” in-groups and out-groups based on race/ethnicity, religion, politics, national affiliation and more.

The philosopher Alain Badiou (2012) suggests that love is what facilitates this, because “in love the other tries to approach ‘the being of the other.’ In love the individual goes beyond himself, beyond the narcissistic…you go to take on the other, to make him or her exist with you, as he or she is.” ( 18) Schwab (1988, in Uraña, 2017) sees love as a force that allows “coming to the other in recognition of the negative in the self.” Abhik Roy (n.d.) draws on Hindu spiritual traditions to call for “viewing ourselves in others” and engaging in authentic dialogue with strangers without either distancing ourselves from the other or objectifying them on the basis of their differences with us. It is this power of love for rising above differences – finding some measure of love for those whom we find hard to love – that interests me, in terms of how we can use this force in transcultural dialogues.

18) Schwab (1988, in Uraña, 2017) sees love as a force that allows “coming to the other in recognition of the negative in the self.” Abhik Roy (n.d.) draws on Hindu spiritual traditions to call for “viewing ourselves in others” and engaging in authentic dialogue with strangers without either distancing ourselves from the other or objectifying them on the basis of their differences with us. It is this power of love for rising above differences – finding some measure of love for those whom we find hard to love – that interests me, in terms of how we can use this force in transcultural dialogues.

Of course this is challenging, and risky, especially when crossing lines of privilege and power. But lines of power in any social group are generally multiple, complex, variegated, overlapping, shifting, and fraught with tension. The aim does not have to be to resolve those tensions as much as to use the tension in generative ways. Irigary (1996) sees love as an “intermediary” that refigures Hegelian dialectical relations not by synthesizing them into a new whole (as Hegel would), but by serving as a passage between dialectical opposites without one side being sacrificed to the other. This involves defying binaries of either/or, us/them, true/false logics that undergird Western thought: challenging the ontologies that hold things apart.

sees love as an “intermediary” that refigures Hegelian dialectical relations not by synthesizing them into a new whole (as Hegel would), but by serving as a passage between dialectical opposites without one side being sacrificed to the other. This involves defying binaries of either/or, us/them, true/false logics that undergird Western thought: challenging the ontologies that hold things apart.

This is not just a psychological or philosophical matter. As an educational researcher, I am interested in how to create spaces where “splitting” does not happen or is interrupted and transformed when it does. Empirically, we might identify structures, politics, policies, and practices that either promote or mitigate against such splitting.

Tensions for education and social transformation

How do we reconcile the idea of accepting others, as they are, with that of teaching, developing, socializing, re-socializing, emancipating, empowering, or decolonizing others…or changing the world? This is a tension that is central to all educational and revolutionary work. What is the role of teachers, leaders, guides or mentors in leading others to freedom or growth? Who decides just how individuals, groups, or society “should” change? Are there loving ways to support others (and ourselves) in growing without imposing particular kinds of growth on anyone?

bell hooks (2000) argues that a loving approach to pedagogy does not mean accepting whatever people do or think. True love involves helping others to stretch and grow, even if that growth is at times uncomfortable.

Freire (1978), in his “pedagogy of the heart,” doesn’t call on people to try to change people, exactly, but to use our wisdom, knowledge, skills and experience to help liberate others, to bring them to greater consciousness, and to support their full expansion as human beings. But again, who does the liberating, or helping, and who decides just how others “should” grow? In educational work, it is difficult to escape the teleological position that presumes that some people are more fully conscious, more highly developed, or more advanced than others, and that it is the work of those greater experts to draw novices into a developmental path – even if, for Freire, the process should be dialogical.

Freire (1978), in his “pedagogy of the heart,” doesn’t call on people to try to change people, exactly, but to use our wisdom, knowledge, skills and experience to help liberate others, to bring them to greater consciousness, and to support their full expansion as human beings. But again, who does the liberating, or helping, and who decides just how others “should” grow? In educational work, it is difficult to escape the teleological position that presumes that some people are more fully conscious, more highly developed, or more advanced than others, and that it is the work of those greater experts to draw novices into a developmental path – even if, for Freire, the process should be dialogical.

In an edited volume about love in relation to childhood, teaching, and learning, Gail M. Boldt and Paula M. Salvio (2016) explore the contradictions and tensions that are set up in non-dialogical approaches to education, when teachers are simultaneously expected to love their students, and to mold and shape them in particular ways. They argue that to really understand the dynamics of power in love, we need to consider psychodynamic processes, in which people (teachers, students, parents) project their own feelings of inadequacy, loss of control, frustration, confusion or pain onto students when students do not conform to their expectations or respond in the ways we think they should.

Putting these ideas together, as an educator, I am interested in what helps people to see others (truly and deeply), and supports them in growing, without trying to change them per se. How do we support growth and learning (for ourselves and others), without creating resistance, projecting our own frustration or hurts onto others, and without presuming that any one of us knows exactly how to help others (or ourselves) to grow, or how to transform the world? As an ethnographer, I am interested in studying spaces and places where these things become (more) possible, and identifying factors and conditions that cultivate them.

Love as an impetus for change

Love and education do not substitute for social action and structural change, but an accompaniment to and motor for that action. Getting in touch with deep feelings of connection and empathy for other human beings may propel us to take action to reduce suffering. Certainly, love can go hand in hand with anger, rage and indignation. Indeed, a love that seeks to counter the forces that divide and oppress must allow room for such emotions to be expressed as well. The element of love is just that which helps us rise above the resistances and blocks that we put up to fully seeing others, and to supporting their growth.

Again, we can consider this an empirical question, not just a psychological or philosophical one. What practices, processes, politics and pedagogies can help people to see themselves in others – e.g. the images that arise daily: those whose homes were flooded in the Caribbean, India, Bangladesh, Florida, and more, or burnt to the ground in California and the northwest; the young Black, Native and transgender people who have lost their lives at the hands of police officers; police officers who were themselves killed doing what they thought was their civic duty; those killed in mass shootings; and so much more random and patterned violence of all kinds? Once people “see the other in themselves,” what actions are they willing to take, that they might not otherwise? And, what gets in the way of empathy?

Grounding the study of love

I am not a philosopher, psychologist or theologian, so I am undoubtedly out of my depth in conceptualizing love in these ways. Professionally, my forays into “love” have been anchored in my work as a pedagogue, and an ethnographer of children’s experiences in homes, communities, classrooms and other contexts. This pushes me to take on a different kind of challenge: What does love have to do with ethnography, and how can we possibly “study” love on the ground? I offer a few possibilities here – and once again, invite further conversation.

Love as a tool in ethnography

Ethnography at its best calls on us to see through the eyes of others, to adopt “emic” viewpoints, to understand local meanings, values, and ideologies. Love as a force that helps us to suspect our own egos, let go of our need to be “right,” and see the other in ourselves, or ourselves in others, can serve as a useful tool to expand our ways of seeing ethnographically. Transcultural dialogue, grounded in a willingness to try to see how others see, and to move past lenses of separation, can assist in expanding our vision, and understanding better the lives of people we “study.”

In the ethnographic methods class that accompanies B-Club, we follow Sandra Harding’s (2016) calls for “creat(ing) missing diversity in research communities” in order to bring novel kinds of insights to research projects. In our classes and on our team, we try to work with the fact that we are people of different ages, genders, social positions, cultural, linguistic, racial/ethnic and social class backgrounds, who are therefore likely to see the world in different ways. We considered why one student highlighted gender issues, and another social class. We wrestle with how and why we each noticed what we noticed, missed what we missed, and interpreted things in particular ways. What was foregrounded? Backgrounded? Left out? Who did we see as the protagonists of actions, or the objects of them? How did we take the messiness of life and transform it into a neat narrative, with a beginning, middle, and end? What, to us, was the story? From what or whose perspective did we narrate the events? We aimed to learn from all of these ways of seeing in order to enrich our own, and to see collectively in more whole and complete ways.

Working with children offers us many opportunities to try to see the world with fresh eyes, and in our work at B-Club we continuously push against the “adult ideological viewpoint” as we try to see how children understand the world they are growing in to. This doesn’t mean abandoning the critical analyses we may bring based on our greater number of years on the planet; it just means holding them lightly, and seeing how they fit with children’s views of their worlds; considering that there can be different truths, or different ways of understanding the complexities of the world. Most importantly, we might learn from kids.

It was listening to children that most opened my mind to seeing possibility, not just problems, and to considering things that had never occurred to me before. The children of today are growing up in a reality that is different than any of us have experienced, and we can learn to see in new ways by attending to their views. As the Guatemalan poet Otto René Castillo wrote, “It is beautiful to love the world with the eyes of those not yet born” – which I take to mean seeing with the eyes of those who have not yet been damaged by the world we are bequeathing to them.

Seeing the affective/spiritual dimensions of human interaction on the ground

This is a slightly different way of approaching the study of “love” – trying to see affective dimensions of human experience in interactions on the ground. Let me suggest a few possibilities:

–Fred Erickson (personal communication) suggests that we look for where students’ eyes “light up” – that spark of enthusiasm that is an indicator of their inner engagement (or “animation”) with words, ideas, people. At B-Club we try to follow kids to see where they light up. Because kids have great freedom of movement in our club (unlike in most classrooms), we can see what they choose to do, who they choose to interact with, in what language, in what ways. Where and how do they connect? Retreat? Withdraw? Move on? This is a way of grounding our study of love, as in love for the things we are teaching and learning, and the people we are teaching and learning with.

–We can look at love as a quality of interaction, such as in the disposition to orient to others or not. We can consider the conditions that support people in stepping in to relationships, and crossing borders (linguistic, cultural, and more), as well as those that may keep them from doing so. Where, when and how are different kinds of borders policed? Where, when and how are they more safely crossed?

–We can look at this in relation to language: Where and how do people freely mix languages or language forms? Where and when do they cut off aspects of their own linguistic repertoires? (See Orellana and Rodriguéz, 2016 for a discussion of how dominant language ideologies constrained the full deployment of linguistic repertoires at B-Club, even as participants displayed tremendous flexibility and versatility in reading both the word and the world.)

–We can look at overt and covert expressions of love, by children and adults. In B-Club, we found that children very freely expressed love to adults, in both spoken and written words, and in physical gestures. Adults, having been socialized not to cross lines of “inappropriate” adult-child school relations, seemed reluctant to speak the word “love.” Adults also tended to follow school rules of giving “sideways hugs” to avoid the sexual innuendos of direct body hugs. (This often resulted in some awkward maneuvers, as adults tried to pull away from children’s spontaneous hugs.) But some people (especially undergraduate participants who may not see themselves as “adults”) kept “forgetting” these no-contact rules. So we can ask who expresses love/affection/caring to whom, in what ways, in what activities or contexts.

–What other emic ways of expressing care and concern are evident? For example, when and how do people attend to each other’s needs and interests? Share materials? Offer assistance, with translation or other tasks? We can identify moments of open disposition, especially those moments of spontaneous cultural or linguistic translation, as well as times when no such translation was offered, or requested. Who notices when others are or are not included, and what actions are taken either to include or exclude? Here, some attention to lines of power will undoubtedly become important, as we consider who gets included or excluded, and/or what new categories of power arise.

I had thought my choices were to continue to walk the world as Marjorie Elaine Orellana (my legal name) or to file for an official reversion to my “maiden” name (Marjorie Elaine Faulstich), returning me as the person I once was: the sixth child and third daughter of Anna Marie Walter and Charles Nicholas Faulstich. But this left me feeling tugged between two poles of patriarchy that no longer served my life. I’m not sure I would know how to re-become Margie Faulstich. Nor would I necessarily want to.

I had thought my choices were to continue to walk the world as Marjorie Elaine Orellana (my legal name) or to file for an official reversion to my “maiden” name (Marjorie Elaine Faulstich), returning me as the person I once was: the sixth child and third daughter of Anna Marie Walter and Charles Nicholas Faulstich. But this left me feeling tugged between two poles of patriarchy that no longer served my life. I’m not sure I would know how to re-become Margie Faulstich. Nor would I necessarily want to. person who ever called me Marjorie Elaine. Choosing to be Marjorie E. Laine is about connecting with my father, in my own unique way, and with my self: a version of myself that holds some continuity with the past, while offering a fresh way to move into the future. (Though I must admit, there is a part of me that is declaring: “Fuck the patriarchy” – something little Margie Faulstich would never have dared say.)

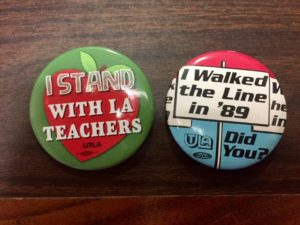

person who ever called me Marjorie Elaine. Choosing to be Marjorie E. Laine is about connecting with my father, in my own unique way, and with my self: a version of myself that holds some continuity with the past, while offering a fresh way to move into the future. (Though I must admit, there is a part of me that is declaring: “Fuck the patriarchy” – something little Margie Faulstich would never have dared say.) I walked the line in ’89. I was a teacher in Los Angeles Unified School District when the teachers’ union (UTLA) led the last teachers’ strike. Thirty years later, I see things from a somewhat different angle. I’m happy to report one big difference between 1989 and now: LA teachers asked for – and won – much more than a modest and well-deserved pay raise for themselves. They advocated loudly and clearly for the rights of children and families in a public education system that has been severely eroded over the years since I left the classroom.

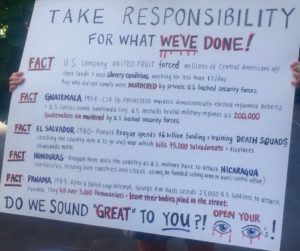

I walked the line in ’89. I was a teacher in Los Angeles Unified School District when the teachers’ union (UTLA) led the last teachers’ strike. Thirty years later, I see things from a somewhat different angle. I’m happy to report one big difference between 1989 and now: LA teachers asked for – and won – much more than a modest and well-deserved pay raise for themselves. They advocated loudly and clearly for the rights of children and families in a public education system that has been severely eroded over the years since I left the classroom. nd, and whether you believe in laws of kharma and the spiritual interconnectedness of life on this planet or not, there is plenty of evidence that the “crises” we see today were initiated long ago by actions that our country took. And the actions we take today will have profound effects on the future.

nd, and whether you believe in laws of kharma and the spiritual interconnectedness of life on this planet or not, there is plenty of evidence that the “crises” we see today were initiated long ago by actions that our country took. And the actions we take today will have profound effects on the future. ional sovereignty, borders, and the rule of law. They are achieved militarily – i.e. through violence.

ional sovereignty, borders, and the rule of law. They are achieved militarily – i.e. through violence.

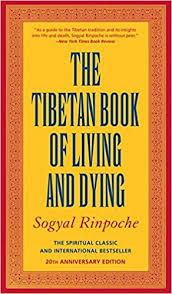

Sogyal Rinpoche’s interpretation and elaboration of The Tibetan Book of the Dead (in The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying) offers a refreshingly different perspective on life and death than the dominant “denial” that permeates modern western culture. Rinpoche suggests how “hollow and futile life can be, when it’s founded on a false belief in continuity and permanence” (p. 17). He describes the way most people live: “Hypnotized by the thrill of building, we have raised the houses of our lives on sand. This world can seem marvelously convincing until death collapses the illusion and evicts us from our hiding place” (p. 16).

Sogyal Rinpoche’s interpretation and elaboration of The Tibetan Book of the Dead (in The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying) offers a refreshingly different perspective on life and death than the dominant “denial” that permeates modern western culture. Rinpoche suggests how “hollow and futile life can be, when it’s founded on a false belief in continuity and permanence” (p. 17). He describes the way most people live: “Hypnotized by the thrill of building, we have raised the houses of our lives on sand. This world can seem marvelously convincing until death collapses the illusion and evicts us from our hiding place” (p. 16).

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood, As part of my fall sabbatical, I had the opportunity to visit Tlatempo, Mexico, a small town in the hills above Cuernavaca that was partly destroyed in the recent earthquake. About half the houses in the town were located directly on an earthquake fault, and they were reduced to rubble. The community school also had crumbled.

As part of my fall sabbatical, I had the opportunity to visit Tlatempo, Mexico, a small town in the hills above Cuernavaca that was partly destroyed in the recent earthquake. About half the houses in the town were located directly on an earthquake fault, and they were reduced to rubble. The community school also had crumbled.

I make a public plea in defense of love and education here: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/in-defense-of-love-and-education_us_59f2489be4b05f0ade1b55ea

I make a public plea in defense of love and education here: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/in-defense-of-love-and-education_us_59f2489be4b05f0ade1b55ea and one that helps us get in touch with our feelings and spirits more than our minds, seeking “positivity resonance” (which Frederickson, 2013:10, defines as “micro-moment(s) of warmth and connection that you share with another living being”) over opposition.

and one that helps us get in touch with our feelings and spirits more than our minds, seeking “positivity resonance” (which Frederickson, 2013:10, defines as “micro-moment(s) of warmth and connection that you share with another living being”) over opposition. While most working from a left, progressive, “critical,” or revolutionary tradition have focused on love for and within oppressed populations, Sandoval (2014) suggests that love can help “transit all citizen-subjects, regardless of social class, toward a differential mode of consciousness.” James Baldwin (1963), as well, saw love as humanizing force for all people, including for oppressors who project their own unresolved pain onto the oppressed.

While most working from a left, progressive, “critical,” or revolutionary tradition have focused on love for and within oppressed populations, Sandoval (2014) suggests that love can help “transit all citizen-subjects, regardless of social class, toward a differential mode of consciousness.” James Baldwin (1963), as well, saw love as humanizing force for all people, including for oppressors who project their own unresolved pain onto the oppressed.  Baldwin saw the opposite of love – hatred – as a force that does not just dehumanize the object of hatred, but that destroys as well the one who hates.

Baldwin saw the opposite of love – hatred – as a force that does not just dehumanize the object of hatred, but that destroys as well the one who hates. I Am My Language: Discourses of Women and Children in the Borderlands.. Laura Rendón builds on Eduardo Galeano’s idea of “sentipensante” – the marriage of thought and feeling – as a foundation for pedagogy, learning and teaching in her book, Sentipensante Pedagogy. Sandoval (2014) writes about those aspects of human experience that “function outside of speech, outside of academic criticism” and that are not expressable in words. (Indeed, she speaks directly to the challenges I face in trying to pin love down in words here.)

I Am My Language: Discourses of Women and Children in the Borderlands.. Laura Rendón builds on Eduardo Galeano’s idea of “sentipensante” – the marriage of thought and feeling – as a foundation for pedagogy, learning and teaching in her book, Sentipensante Pedagogy. Sandoval (2014) writes about those aspects of human experience that “function outside of speech, outside of academic criticism” and that are not expressable in words. (Indeed, she speaks directly to the challenges I face in trying to pin love down in words here.) 18) Schwab (1988, in Uraña, 2017) sees love as a force that allows “coming to the other in recognition of the negative in the self.” Abhik Roy (n.d.) draws on Hindu spiritual traditions to call for “viewing ourselves in others” and engaging in authentic dialogue with strangers without either distancing ourselves from the other or objectifying them on the basis of their differences with us. It is this power of love for rising above differences – finding some measure of love for those whom we find hard to love – that interests me, in terms of how we can use this force in transcultural dialogues.

18) Schwab (1988, in Uraña, 2017) sees love as a force that allows “coming to the other in recognition of the negative in the self.” Abhik Roy (n.d.) draws on Hindu spiritual traditions to call for “viewing ourselves in others” and engaging in authentic dialogue with strangers without either distancing ourselves from the other or objectifying them on the basis of their differences with us. It is this power of love for rising above differences – finding some measure of love for those whom we find hard to love – that interests me, in terms of how we can use this force in transcultural dialogues. sees love as an “intermediary” that refigures Hegelian dialectical relations not by synthesizing them into a new whole (as Hegel would), but by serving as a passage between dialectical opposites without one side being sacrificed to the other. This involves defying binaries of either/or, us/them, true/false logics that undergird Western thought: challenging the ontologies that hold things apart.

sees love as an “intermediary” that refigures Hegelian dialectical relations not by synthesizing them into a new whole (as Hegel would), but by serving as a passage between dialectical opposites without one side being sacrificed to the other. This involves defying binaries of either/or, us/them, true/false logics that undergird Western thought: challenging the ontologies that hold things apart.

In my last blog I had promised to begin unpacking a series of seeming tensions between a “critical” stance (i.e. focused on naming and changing power relations in the world) and a more “spiritual” one (i.e. focused on compassion, love and acceptance).

In my last blog I had promised to begin unpacking a series of seeming tensions between a “critical” stance (i.e. focused on naming and changing power relations in the world) and a more “spiritual” one (i.e. focused on compassion, love and acceptance). in coalition with others to respond to the matters of the day, taking action on immediate items (e.g. defending immigrant rights), and being prepared to respond to whatever comes up. Be mentally, emotionally and physically prepared to respond to hate, with love and a firm stance of solidarity for anyone who is attacked.

in coalition with others to respond to the matters of the day, taking action on immediate items (e.g. defending immigrant rights), and being prepared to respond to whatever comes up. Be mentally, emotionally and physically prepared to respond to hate, with love and a firm stance of solidarity for anyone who is attacked.

While I don’t like my tax dollars going to funding the U.S. war machine, I do believe in paying taxes to offset my use of the world’s resources, and if the government isn’t going to tax me, I will just have to tax myself. I am gravely concerned that the Trump presidency can set us back on the ticking clock to stall Climate Change in ways that we simply cannot afford.

While I don’t like my tax dollars going to funding the U.S. war machine, I do believe in paying taxes to offset my use of the world’s resources, and if the government isn’t going to tax me, I will just have to tax myself. I am gravely concerned that the Trump presidency can set us back on the ticking clock to stall Climate Change in ways that we simply cannot afford.

nature.

nature. r sure, there are exceptional scholars who traverse the divide between heart and mind, and between criticality and love, with grace and power. Paolo Freire, bell hooks, Gloria Anzaldúa, Sofía Villenas are just a few who come to mind. These heart-centered scholars inspire and embolden me.

r sure, there are exceptional scholars who traverse the divide between heart and mind, and between criticality and love, with grace and power. Paolo Freire, bell hooks, Gloria Anzaldúa, Sofía Villenas are just a few who come to mind. These heart-centered scholars inspire and embolden me.

B-Club 2016 is in full swing now. The shift in perspective always surprises me, though I’ve seen it every year. The initial confusion that most of the young adult participants have when they first enter this space begins to fall away. Their critiques of it get suspended, at least a little. Their resistances erode. They begin to open themselves to the experience, to develop a new understanding of what we are doing, and contemplate why. They start asking new questions about the nature of teaching and learning, and thinking about transformative education in new ways.

B-Club 2016 is in full swing now. The shift in perspective always surprises me, though I’ve seen it every year. The initial confusion that most of the young adult participants have when they first enter this space begins to fall away. Their critiques of it get suspended, at least a little. Their resistances erode. They begin to open themselves to the experience, to develop a new understanding of what we are doing, and contemplate why. They start asking new questions about the nature of teaching and learning, and thinking about transformative education in new ways. idden in the grassy field upstairs, telling scary stories as they went. Ramón and Amber led a group in finishing the paper maché piñatas they started two weeks ago, talking about this familiar cultural practice as they dipped strips of paper into gooey concoctions and laid the strips over balloons. The art table continued to attract a small but faithful group of budding artists – though mostly girls, as Greg noted in his reflections on the gendering of space and activities.

idden in the grassy field upstairs, telling scary stories as they went. Ramón and Amber led a group in finishing the paper maché piñatas they started two weeks ago, talking about this familiar cultural practice as they dipped strips of paper into gooey concoctions and laid the strips over balloons. The art table continued to attract a small but faithful group of budding artists – though mostly girls, as Greg noted in his reflections on the gendering of space and activities. (That’s one of our theory-practice conversations: how can we create activities that defy easy gender binaries, and help all kids to expand their repertoires?) Kids stop by the letter-writing table, book corner, or journal writing section whenever they fell like it, integrating literacy into their play with the creative encouragement of Grugs.

(That’s one of our theory-practice conversations: how can we create activities that defy easy gender binaries, and help all kids to expand their repertoires?) Kids stop by the letter-writing table, book corner, or journal writing section whenever they fell like it, integrating literacy into their play with the creative encouragement of Grugs.  For example, last week Michiko played a game of Hide and Seek with three first graders. She explained:

For example, last week Michiko played a game of Hide and Seek with three first graders. She explained: