So what was I doing in Padova, Italy (known to some English speakers as Padua) this summer?

Six years ago I learned about the Fulbright Specialist Roster, a program supporting short (2-6 week) project-based exchanges to build connections around the world. This is part of the Fulbright Program’s mission of “building mutual understanding between nations, advancing knowledge across communities, and improving lives around the world.”

My youngest child was in college, and I had the freedom of an empty nest. I wanted to spread my wings and see more of the world. I thought I could offer my skills and experiences in some kind of international exchange. I applied and was accepted.

For the next few years, I scoured lists of Fulbright projects, looking for a match for my professional skills. Universities around the world sought experts on agriculture, business, finance, engineering and more. My academic skills seemed so impractical, even within my own field of Education. For example, the Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission sought someone to help with their “Functional and Technical Competency Development Program.” The Jordan Ministry of Higher Education wanted help with university president selection. I doubted these institutes would see my work with children as helpful for such tasks.

And then the pandemic hit and travel came to a screeching halt.

But shortly before life closed in on itself and international contact got confined to little boxes on Zoom, I met a young scholar from Italy. Lisa Bugno had read my book, Immigrant Children in Transcultural Spaces: Language, Learning and Love. She wanted to know more about B-club, the afterschool program featured in this book, and the university-community partnership that had spawned it.

Perhaps this is an answer to the question I posed in a previous post: Why write? And why share our writing? Here was an answer: because it connects us with other like-minded people. Because someone – even just one person! – may find inspiration in what we share.

When the heavy veil of pandemic lockdowns lifted, the Fulbright Specialist Roster seemed to offer an opportunity to deepen my collaboration with Lisa, and for me to support the University of Padova’s efforts to forge a community partnership inspired by UCLinks.

So Lisa submitted a proposal to Italy’s Fulbright Commission, and it was approved, and I was cleared for six weeks of living and working in Padova. I would work with Lisa and her colleague Luca Agostinetti – a two-person program on Intercultural Education within the Department of Philosophy, Sociology, Pedagogy and Applied Psychology – and support them in their ongoing work of forging a university-community partnership to advance education for students from migrant and refugee backgrounds in Padova’s public schools.

I would also get to experience intercultural education as I learned about schools in Italy, adapted to a new local environment, struggled to communicate in Italian, and engaged in new everyday cultural practices for six weeks.

The University of Padova

And so to stay true to the commitments to socially conscious travel that I named in my last blogpost, next up I’ll share a little of what I did while I was there, in words and photos.

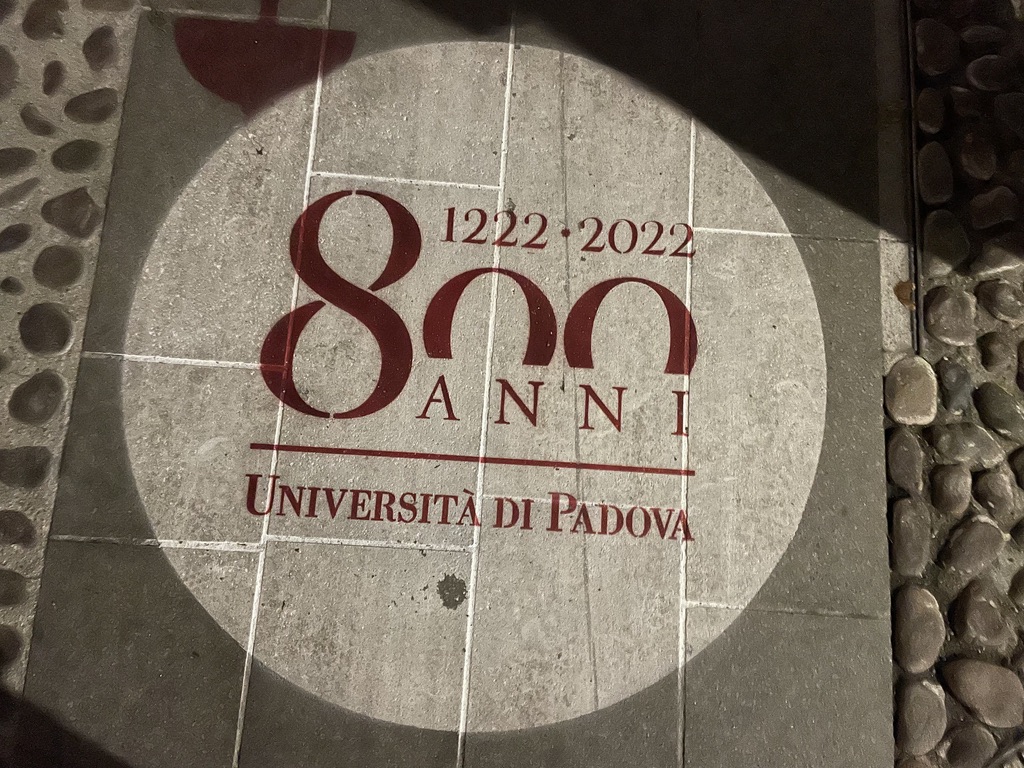

But first, a little about the University of Padova, which is celebrating its 800th anniversary this year. Learning about the University of Padova and its fascinating history was one of the many highlights of this trip.

The University of Padova was formed in 1222 (take that in!), by a group of students and faculty who broke away from the University of Bologna because they wanted more academic freedom.

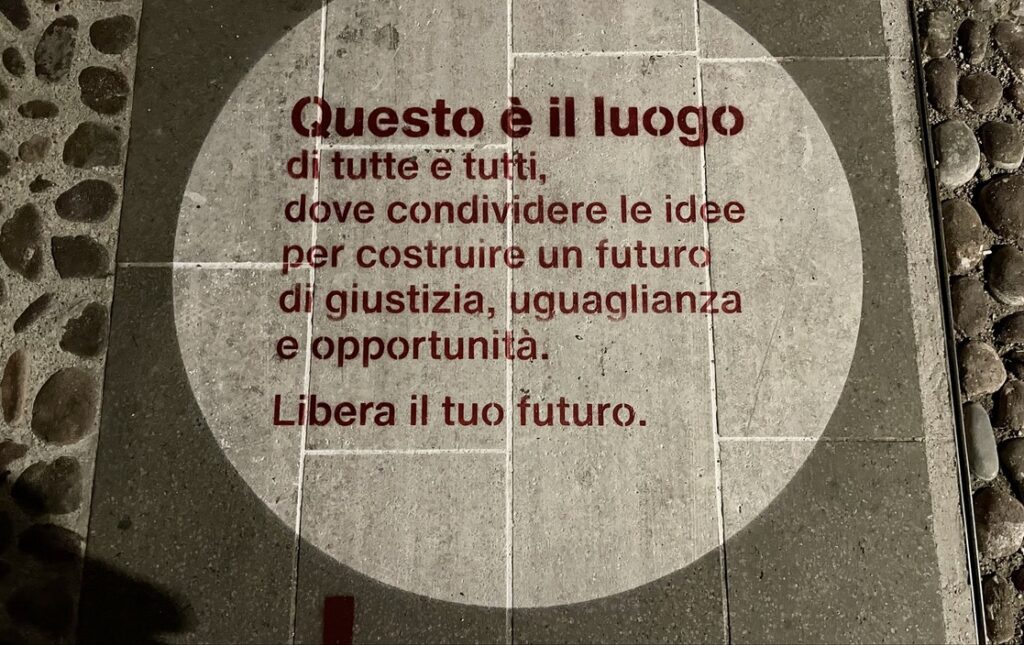

This was stenciled on sidewalks all around the town, celebrating the university’s 800 years.

“This is the place where one and all can share ideas to build a future of justice, equality and opportunity. Liberate your future!” (translation mine, with assistance from Google)

In its early years, students elected their own teachers and rectors; the directors were chosen from their own ranks, and their names are inscribed on plaques on the wall in Palazzo Bo, one of the oldest halls in the university (formerly an inn).

The university boasts of having awarded the first university degree (“lauriate”) to a woman, ever: to Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopea in 1678. Elena was actually schooled at home – the only option for women of her time. Elena was the daughter of a poor peasant woman and a noble father (yes, her mother was his mistress). She was a child prodigy who mastered multiple languages (Greek, Latin, Spanish, French, Hebrew and Arabic). She also studied math, philosophy, theology, music and more. Her father negotiated with the University of Padova to grant her a degree in Philosophy based on her independent studies.

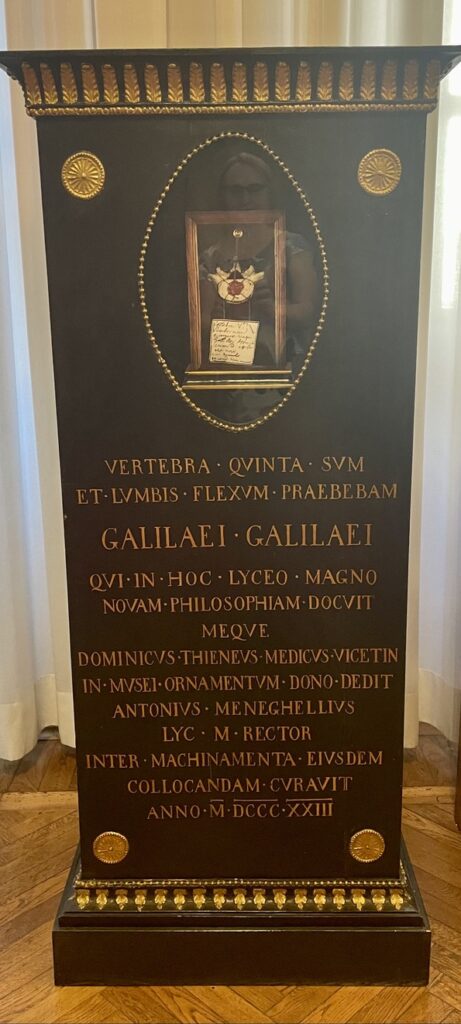

Other interesting facts: Galileo taught at the University of Padova. Both his podium and his rib (the 5th vertebra) are on display in Palazzo Bo, the former-inn-turned-university-hall where many PhD students today are awarded their degrees.

So too are the skulls of professors who donated their bodies to science, which were dissected in the medical theatre while students looked on.

Lisa Bugno took us on a tour of this hall, and was moved to tears by the memory of her own PhD ceremony in this austere space.

We also toured Padova’s Botanical Gardens – which is either the first or second university-associated Botanical Gardens in the world. (The University of Pisa is generally viewed as the first, but Padovans contest this on technicalities).

Visiting the university in July was a special treat, because it was graduation time. Ceremonies for different departments and programs were spread out over the course of several weeks, and I would stumble upon informal celebrations all across town, as students gathered to toast (and roast) their friends, in all kinds of playful ways.

I got to witness some masters’ theses defenses, attended by family and friends, held in this formidable hall.

I got to work with smart, multi-lingual, international graduate and undergraduate students at this university on ethnography and interview data analysis, and learning about their work.

There’s so much more I could share about this fascinating university and town; I’ve only skimmed the surface here. I hope I’ve piqued your interest to learn more. Perhaps an international exchange is in your own future?

Forging University-Community Partnerships: La Mia Escola e Diferente

The real aim of my work was to support Lisa Bugno and Luca Agostinetti’s activities in a university-community-school partnership that is called “La Mia Scuola e Diferente.” This involved getting out of the halls of the university and into the community.

The project name plays with the multiple meanings of “different:” it reclaims the power of diversity in the face of a public that sees difference mostly as a problem. The school that is at the heart of this program is generally referred to as “different” in public discourse because it serves “foreign” students who live in a “ghetto.” And indeed, Italy does not grant birth-right citizenship to the children of migrants, so the children who attend this school, most of whom were born in Italy, are not viewed as Italian, and don’t have the rights of Italian citizenship. They are perpetual foreigners, and how to “include” them in the larger society becomes a problem that schools are expected to solve.

One of the challenges we discussed together this summer was how to reframe difference in the Italian context: how to help students, teachers and other community members to see diversity not as a problem to solve but as a resource. How to see the richness of culture, language and life experiences that families in this marginalized community bring, and that could be honored, sustained, expanded and developed in school? This is at the heart of my own work across the decades.

This is particularly important in this political moment in Italy, where just last week Benito Mussolini’s granddaughter was just elected to presidency, on a mostly anti-immigrant platform.

At the same time, in Padova, as in most communities around the world, not everyone views migrants as problems. There are many who welcome these “foreigners” and who advocate actively for their needs and rights. I met with many, including:

—Maestro Fabio, a dynamic elementary school teacher who is spearheading many efforts to connect with parents and the local community: families who come from China, Serbia, Ghana, Ukraine, Syria, Colombia and more. I visited the school during its summer sessions and spent some time with these smart, funny, energetic kids.

—The director and staff of Fenice Green Energy Park, a center dedicated to educating about green energy, the problems of pollution, and climate change. We toured their facilities and got a glimpse into projects they are bringing to the kids in La Mia Scuola e Diferente.

–The staff of Zalab, makers of documentary films about progressive issues, who run a film-making program with school aged youth.

-Members of the University of Padova’s Psychology Department, who are working at Fabio’s school to provide a safe “nido” for refugee youth to process the traumas they have experienced, and to support their social and emotional well-being.

I also met with other teachers and community members who are working to support im/migrants who have gotten to Italy against all odds, seeking better lives.

This includes Luca Favorin, a renegade Catholic priest who has created a project called Percorso Vita, which provides housing and jobs for migrants. We shared delicious meals at the restaurant he has created, staffed by migrants who bring culinary experiences from their home countries to create gourmet meals in an outdoor setting adorned with images of migrants and representations of their experiences.

I met with Sergio Giordani, the mayor of Padova, a down-to-earth man with a progressive vision for the city, in an austere, centuries-old hall.

I talked with the local newspaper and a local television station about La Mia Scuola e Diferente project.

My own intercultural education

I also got to see and experience a myriad of other things.

I had a hands-on lesson on pasta-making (“oriquetas”) at Lisa’s kitchen table.

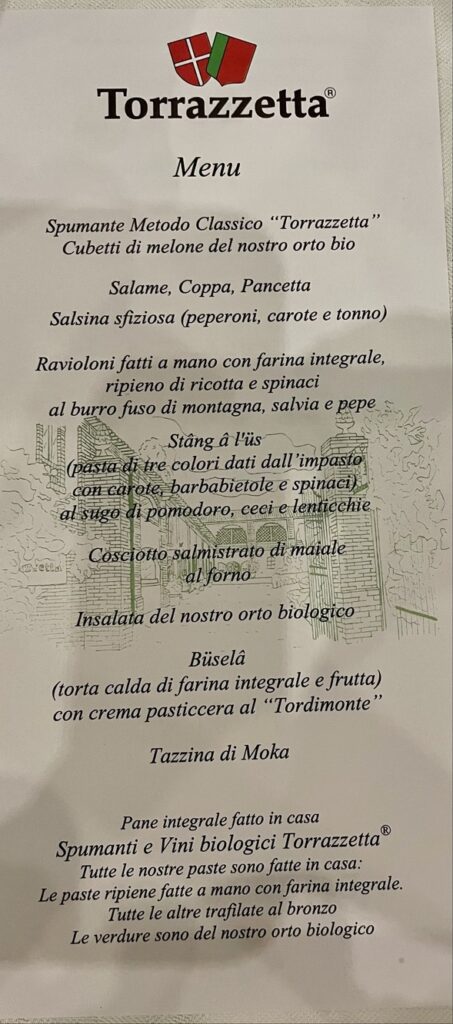

I also went on a wine-tasting tour to a consortium of wineries (Consorzio Tutela Vini Oltrepo Pavese) that are working in ecologically sustainable ways. One of my hosts, Luca Agostinetti, in addition to being an expert on intercultural education, is also an expert sommelier. He and Lisa organized a wine-tasting tour for students in a class they taught on wine and gastronomia. I got to join them. We toured six wineries, with wine-tasting at each of them, and had some amazing meals in Italy’s best “slow food,” farm-to-table style in rural areas that are building agriturismo.

Experiencing daily life in Padova

One of the things I most enjoyed during my six weeks in Padova was the opportunity just to feel the rythms of daily life, to immerse myself in this local context, and to get to know the town. I purchased a used bicycle and virtually every day ventured out to bike and walk around the labyrinthian streets of this historical town.

Of course, I ate amazing food. More importantly, I saw the deep valuing of food in the Italian culture: taking time to eat, to be together, to nurture the body and spirit and soul. Eating just enough, and slowly. Enjoying each bite. Not rushing through oversized meals in the American way. I saw that schools also value food as a way of nurturing young people, educating both body and mind.

This extended to coffee-drinking. Tiny shots of expresso, or small cups of cappuchino. Not the bloated and bloating, sugar-drenched, over-sized Starbucks versions. (“Venti” – what an ugly usurpation of an Italian word!)

These experiences formed my own intercultural education. I had to figure out all the things that newcomers deal with: identifying food in supermarkets, navigating the bus system, getting lost, struggling to communicate with a rudimentary knowledge of the language (more on that in a future blog), and so much more. All of this gave me more empathy for and understanding of what new im/migrants contend with – with far fewer supports and a whole lot more trauma.

I did indulge in some “tourist” experiences as well, through day trips to Venice, Florence, Bologna, the foothills of the Alps, and Bassano del Grappa. In the latter, I experienced the beauty of this land and learned more about its terrible history under Fascism.

Fermente intercultural

In all of this, I hope I fulfilled the Fulbright mission. My own understanding of the world expanded. I came away with a deep sense of appreciation for people all around the world who are doing work like the good-hearted people I met in Padova: facing similar challenges as they try to reframe “diversity” from a problem into possibilities, and address the very real inequities and injustices that abound in different-yet-similar forms around the world.

My aim in this blog is to share just a little of what I have learned with interested readers, and to preserve a summary of the experiences for myself. I hope I have fairly, if only very briefly, represented all the people and organizations I got to know.

Importantly, my collaboration with the people I met in Padova is not finished. In many ways, it’s just beginning. It takes a long time to forge cross-cultural understandings, and I only scratched the surface in my six weeks there. Luca Agostinetti described this work as “fermente intercultural.” Intercultural exchanges are like good wine: they take a long time to come to fruition. They require continuous attention (as in the “metodo clasico” of prosecco-production, in which wine bottles have to be turned twice a day for many years).

At the last winery we visited on our tour, the owners opened a 35-year-old bottle of prosecco for us. We toasted each other in a cellar surrounded by a million bottles of wine, all fermenting, awaiting their time to be savored and appreciated in the world.

I make a public plea in defense of love and education here: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/in-defense-of-love-and-education_us_59f2489be4b05f0ade1b55ea

I make a public plea in defense of love and education here: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/in-defense-of-love-and-education_us_59f2489be4b05f0ade1b55ea and one that helps us get in touch with our feelings and spirits more than our minds, seeking “positivity resonance” (which Frederickson, 2013:10, defines as “micro-moment(s) of warmth and connection that you share with another living being”) over opposition.

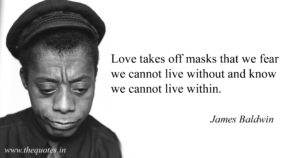

and one that helps us get in touch with our feelings and spirits more than our minds, seeking “positivity resonance” (which Frederickson, 2013:10, defines as “micro-moment(s) of warmth and connection that you share with another living being”) over opposition. While most working from a left, progressive, “critical,” or revolutionary tradition have focused on love for and within oppressed populations, Sandoval (2014) suggests that love can help “transit all citizen-subjects, regardless of social class, toward a differential mode of consciousness.” James Baldwin (1963), as well, saw love as humanizing force for all people, including for oppressors who project their own unresolved pain onto the oppressed.

While most working from a left, progressive, “critical,” or revolutionary tradition have focused on love for and within oppressed populations, Sandoval (2014) suggests that love can help “transit all citizen-subjects, regardless of social class, toward a differential mode of consciousness.” James Baldwin (1963), as well, saw love as humanizing force for all people, including for oppressors who project their own unresolved pain onto the oppressed.  Baldwin saw the opposite of love – hatred – as a force that does not just dehumanize the object of hatred, but that destroys as well the one who hates.

Baldwin saw the opposite of love – hatred – as a force that does not just dehumanize the object of hatred, but that destroys as well the one who hates. I Am My Language: Discourses of Women and Children in the Borderlands.. Laura Rendón builds on Eduardo Galeano’s idea of “sentipensante” – the marriage of thought and feeling – as a foundation for pedagogy, learning and teaching in her book, Sentipensante Pedagogy. Sandoval (2014) writes about those aspects of human experience that “function outside of speech, outside of academic criticism” and that are not expressable in words. (Indeed, she speaks directly to the challenges I face in trying to pin love down in words here.)

I Am My Language: Discourses of Women and Children in the Borderlands.. Laura Rendón builds on Eduardo Galeano’s idea of “sentipensante” – the marriage of thought and feeling – as a foundation for pedagogy, learning and teaching in her book, Sentipensante Pedagogy. Sandoval (2014) writes about those aspects of human experience that “function outside of speech, outside of academic criticism” and that are not expressable in words. (Indeed, she speaks directly to the challenges I face in trying to pin love down in words here.) 18) Schwab (1988, in Uraña, 2017) sees love as a force that allows “coming to the other in recognition of the negative in the self.” Abhik Roy (n.d.) draws on Hindu spiritual traditions to call for “viewing ourselves in others” and engaging in authentic dialogue with strangers without either distancing ourselves from the other or objectifying them on the basis of their differences with us. It is this power of love for rising above differences – finding some measure of love for those whom we find hard to love – that interests me, in terms of how we can use this force in transcultural dialogues.

18) Schwab (1988, in Uraña, 2017) sees love as a force that allows “coming to the other in recognition of the negative in the self.” Abhik Roy (n.d.) draws on Hindu spiritual traditions to call for “viewing ourselves in others” and engaging in authentic dialogue with strangers without either distancing ourselves from the other or objectifying them on the basis of their differences with us. It is this power of love for rising above differences – finding some measure of love for those whom we find hard to love – that interests me, in terms of how we can use this force in transcultural dialogues. sees love as an “intermediary” that refigures Hegelian dialectical relations not by synthesizing them into a new whole (as Hegel would), but by serving as a passage between dialectical opposites without one side being sacrificed to the other. This involves defying binaries of either/or, us/them, true/false logics that undergird Western thought: challenging the ontologies that hold things apart.

sees love as an “intermediary” that refigures Hegelian dialectical relations not by synthesizing them into a new whole (as Hegel would), but by serving as a passage between dialectical opposites without one side being sacrificed to the other. This involves defying binaries of either/or, us/them, true/false logics that undergird Western thought: challenging the ontologies that hold things apart.

B-Club 2016 is in full swing now. The shift in perspective always surprises me, though I’ve seen it every year. The initial confusion that most of the young adult participants have when they first enter this space begins to fall away. Their critiques of it get suspended, at least a little. Their resistances erode. They begin to open themselves to the experience, to develop a new understanding of what we are doing, and contemplate why. They start asking new questions about the nature of teaching and learning, and thinking about transformative education in new ways.

B-Club 2016 is in full swing now. The shift in perspective always surprises me, though I’ve seen it every year. The initial confusion that most of the young adult participants have when they first enter this space begins to fall away. Their critiques of it get suspended, at least a little. Their resistances erode. They begin to open themselves to the experience, to develop a new understanding of what we are doing, and contemplate why. They start asking new questions about the nature of teaching and learning, and thinking about transformative education in new ways. idden in the grassy field upstairs, telling scary stories as they went. Ramón and Amber led a group in finishing the paper maché piñatas they started two weeks ago, talking about this familiar cultural practice as they dipped strips of paper into gooey concoctions and laid the strips over balloons. The art table continued to attract a small but faithful group of budding artists – though mostly girls, as Greg noted in his reflections on the gendering of space and activities.

idden in the grassy field upstairs, telling scary stories as they went. Ramón and Amber led a group in finishing the paper maché piñatas they started two weeks ago, talking about this familiar cultural practice as they dipped strips of paper into gooey concoctions and laid the strips over balloons. The art table continued to attract a small but faithful group of budding artists – though mostly girls, as Greg noted in his reflections on the gendering of space and activities. (That’s one of our theory-practice conversations: how can we create activities that defy easy gender binaries, and help all kids to expand their repertoires?) Kids stop by the letter-writing table, book corner, or journal writing section whenever they fell like it, integrating literacy into their play with the creative encouragement of Grugs.

(That’s one of our theory-practice conversations: how can we create activities that defy easy gender binaries, and help all kids to expand their repertoires?) Kids stop by the letter-writing table, book corner, or journal writing section whenever they fell like it, integrating literacy into their play with the creative encouragement of Grugs.  For example, last week Michiko played a game of Hide and Seek with three first graders. She explained:

For example, last week Michiko played a game of Hide and Seek with three first graders. She explained: