This blog reports on a visit to the ICE Processing Center in Adelanto, California, organized by the Center for the Study of International Migration at UCLA.

We headed out from UCLA around 9:30 am on Thursday, November 14. Five of us packed in to the car: two Sociology professors (Roger Waldinger and César Ayala), two graduate students and I. Another student was to meet us near the Detention Center. The freeway was remarkably open, and we sailed across the City of Angels and out into the southeastern desert. In the car we discussed what we each anticipated the visit would involve, and realized that most of us had rather little idea of what to expect.

Ninety minutes later we encountered a sign telling us we had arrived at Adelanto: “The city of unlimited possibilities.” The irony was not lost on us.

We met at a coffee shop with our contact to the facilities, a visitor-volunteer who spends countless hours as well as her own money to support migrants. She keeps records about who is housed in the facilities, the status of their asylum cases, and other basic information. She helps them advocate for their rights and secure things they need, including visitors, basic supplies, and access to lawyers, as well as information, help and basic goods if and when they are released. We were provided with a list of asylum seekers who don’t have families and friends in the area and who have not had visitors in a long time.

The facilities were tucked in a far corner of this desert town, itself already well isolated from the larger metropolitan area of Los Angeles. A sign bears the GEO label; this “Modified Community Correctional Facility” is actually a complex of facilities, including a prison and two migration detention center buildings, all run by the GEO group, a for-profit management company that claims it is “committed to providing leading, evidence-based rehabilitation programs to individuals while in-custody and post-release into the community.”

The facilities were tucked in a far corner of this desert town, itself already well isolated from the larger metropolitan area of Los Angeles. A sign bears the GEO label; this “Modified Community Correctional Facility” is actually a complex of facilities, including a prison and two migration detention center buildings, all run by the GEO group, a for-profit management company that claims it is “committed to providing leading, evidence-based rehabilitation programs to individuals while in-custody and post-release into the community.”

Isolation and separation are a large part of how the detention system works, like the prison system. People in detention are removed from the larger society – kept out of sight and thus out of mind. They are further separated and isolated within the centers, with visits possible only under carefully controlled situations. I spoke with a migrant from Ghana who told me there were three other Ghaneans in the facility, but they were (seemingly deliberately) housed in separate units, and had been discouraged from talking to each other. Men and women are also separated, not surprisingly, with different visiting days for each. I don’t know where transgender people – a growing group of refugee seekers escaping persecution in their home countries – would be housed. Thursdays were designated for men.

We walked into the reception area. A framed poster behind the front desk read, “General Library” and sported an image of neatly organized books. To the right of the desk was a notice for “Attorney Appointments” with a phone number. There were two bank-teller-like machines across from the desk with a potted fern in between. These machines boasted “Send money the fast, easy, reliable way.” Other signs on the walls included one that dec

We walked into the reception area. A framed poster behind the front desk read, “General Library” and sported an image of neatly organized books. To the right of the desk was a notice for “Attorney Appointments” with a phone number. There were two bank-teller-like machines across from the desk with a potted fern in between. These machines boasted “Send money the fast, easy, reliable way.” Other signs on the walls included one that dec lared, “Keep Detention Safe” and proclaimed “zero tolerance” for sexual abuse and assault. The waiting area off to the side was lined with blue plastic chairs, and sported another series of framed posters: pristine images from around the facilities, all eerily devoid of people.

lared, “Keep Detention Safe” and proclaimed “zero tolerance” for sexual abuse and assault. The waiting area off to the side was lined with blue plastic chairs, and sported another series of framed posters: pristine images from around the facilities, all eerily devoid of people.

A guard in a powdered blue button-down shirt and uniform grey pants welcomed us, though “welcome” is surely not the right word. Most of the receptionists and guards that we interacted with that day avoided eye contact and stuck with the regulations: recording our names and the numbers of the migrants we wanted to visit, collecting our government-issued IDs, handing us keys to lock up our valuables – or not just our valuables, but rather everything we had with us, down to the chapstick I found in my pocket. We were given badges with our visitation numbers. The guards showed little curiosity about why our merry band was there.

One of our members had forgotten to bring his license. Not surprisingly, he was told that he would not be allowed to enter the facilities. This was an awakening to the privilege that many of us operate with: to move about the world without carrying official documentation of our legal status, not expecting to encounter checkpoints where our entry would be barred.

After waiting for some time in the waiting area, we were told we could proceed through the security detector. We were escorted by armed guards through a series of heavily bolted doors, past a window into the guards’ area where we saw a large board filled with handcuffs of different sizes, and into a holding area, where a “Continuum of Care” poster was prominently displayed.

We were then allowed into the visiting area: a room set with small tables and chairs, not unlike the one in the waiting room poster. Five or six men were there, waiting, spaced around the room. We were told where to sit – across from the migrant we had signed up to visit, not next to him. (This arrangement made it hard to hear – a fact that was aggravated by the ambient noise in the room.)

There were strict regulations about how people many could be in the room at the same time, and who could be mixed with whom. No recording instruments were allowed past the waiting area: no phones, notebooks, pencils or pens. At the end of the visits, we were allowed to write down the names and bunk/dorm numbers of the migrants, and to offer them our contact information – but only under the strict vigilance of the guards, who gave us stubby pencils and small scraps of paper. One of my colleagues reached over the desk to borrow a pen to jot something down, and was promptly scolded by the guard: “You should ask to borrow my pen.”

The migrants were all dressed in clean blue prison-like garb, except one older man who was in orange, visiting with a middle-aged woman, three younger women of varying ages, and a baby. We learned from that this man had lived in Los Angeles for 25 years; he had been detained by ICE after a traffic stop, and was now awaiting his deportation hearing.

Later, we asked our guide about the different color uniforms. She explained that those migrants who are deemed “low risk” or “docile” wear blue; red is for those who are considered “belligerent;” orange is for those deemed “in between docile and belligerent.” There is a careful system of monitoring who gets to be in the room at the same time: red and blue are never to mix. Some migrants are also “quarantined” when they are ill.

I met with a migrant whom I’ll call Ronald. Ronald was from Ghana. He had been in detention since December. He had left Ghana in June last year, traveling to Ecuador, then by boat to Colombia, and up through the Panamanian jungle. He said it was “very difficult” and he talked repeatedly about pain –both physical and psychological. I did not get a clear story about Ronald’s asylum case, though he mentioned that someone had wanted him killed. When I asked him what he wanted me to say to the world on his behalf, he said, “I am not a criminal. Not here, not there, and I never will be.” He made clear that he felt he was being treated as one. (We might wonder, just what are refugee seekers to be “rehabilitated” from, in GEO’s Continuum of Care?)

Ronald told me that he works in the cafeteria for 7-8 hours a day. For this, he is paid $1/day. He needs the money to buy items at the prison’s commissary (at heavily marked up prices) or to make phone calls – the phone calls that are promised in a waiting room poster. These phone calls cost $1 per MINUTE.

In the afternoon, I met with another migrant at the other unit of the detention center – this after our group waited for more than an hour. Eduardo (a pseudonym) was from Honduras. His story was that he had been recruited by his uncle, who was a drug lord, into a gang. “I am not a killer,” he told me, and he felt he had to leave Honduras or be killed for his resistance. His asylum case had been denied, but was under appeal. He was afraid for his life, should he be deported back to Honduras. And he had lost contact with his wife and children.

Eduardo teared up as he, like Ronald, told me of his suffering. His immediate concern was physical pain. He had been hospitalized a few days earlier and had returned to find that his things had been stolen (documents and a few items he had purchased in the commissary, his pain medication, and the Claritin that he needed for allergies.) But it was the indignity that he had experienced that seemed most distressing: going in handcuffs to the hospital, then returning, still in great pain, and being told he had to stand in line like everyone else for his dinner. When he couldn’t stand, the guard let him sit down – but then told him he couldn’t eat.

When we parted, Eduardo asked me to call his mother to tell him he was ok. He asked me not to tell her about the pain he was in. But the guard insisted that he write down the number for me. This meant that Eduardo had to translate the phone number into English for the guard. Perhaps it was a problem that arose in the translation or transcription, but when I called that number, and spoke in Spanish asking for Eduardo, I was met with the voice of an angry woman who told me, “Speak in English or get out of this country.”

These are just two of many migrants’ stories. Some eventually pass through the system and are released on bail to await their asylum hearings – like Donaldo, a 21-year-old Cuban who met with César. Donaldo was released a few days later. With help from César and the foundation that supports migrants, he managed to post his $7500 bail, rent the required GPS surveillance device that will be used to track him, buy new clothes (because the clothes migrants bring into detention often do not serve them upon release), purchase a ticket to Tampa, stay over night in Los Angeles, and fly out to stay with relatives. Note: Without the help of foundations that post bail, migrants are left to borrow the money from bondspeople, who charge $1000 plus 20% of the bond. [One of the best ways you can help refugees is to contribute to organizations who post bonds. See below for a links.]

A few migrants may eventually be granted official refugee status. A few may give up on detention and opt to return to their home countries on their own. Others will be deported, to uncertain fates.

***

When we walked out the door at the end of the day I felt a tremendous surge of gratitude for freedoms I take for granted every day: to walk where I want to walk, in the open air, sunshine, or night sky. To eat what and when I choose. To purchase basic supplies, treat my own allergies, and go to the doctor without handcuffs around my wrists. Never mind to live without fear for my life.

Certainly, refugees suffer in many places around the world, not just the Unite States. Thousands are crowded into tents in northern Africa and put onto islands off the coast of Australia. There have been refugees throughout history who have been denied entry to this and other countries, even when we knew they were at risk for being rounded up and sent to their deaths.

But this clinical, neat, clean, prison-like approach seems uniquely American, and driven by a profit motive. Note that GEO’s stock portfolio shows a huge spike in November, 2016, right after Donald Trump was elected.

To me, the overall look and feel of Adelanto’s detention center was eerily reminiscent of the concentration camp I visited outside Munich this summer. Dachau was begun as a work camp, not an extermination camp; but that work was done in service to the nation, by people that the nation did not value as their own. I wonder what other Germans knew about what went on in these camps.

The American detention center system is not an extermination camp, though when we deny asylum we may well be sending people to their deaths. It is not a work camp, though at $1/day migrants’ labor surely contributes to the profits GEO reaps. But the parallels still bear consideration. Surely we can learn from history about the importance of knowing what is being done behind barbed wires, by people our nation deems less than fully human, in our name?

What we can do in the face of this system? I went to Adelanto in order to see with my own eyes the things that my government wants to keep out of view. I wanted to listen to people, hear their stories, and give them a chance to be heard. I wanted to respond to Ronald’s plea: “I need someone to talk with to receive my pain and sadness.” And I wanted to bring migrants’ stories to a larger public, so that no one can say, “But we didn’t know.”

The Center for the Study of International Migration at UCLA will continue to organize monthly visits. If you’d like to join us, please contact me or reach out the Center. We are also organizing letter-writing campaigns and a penpal program with migrants. This in addition to our work bringing together diverse forms of scholarship about migration matters. Check out the calendar of events at https://www.international.ucla.edu/migration.

See also https://www.international.ucla.edu/migration/article/210862 for a list of actions you can take in support of migrants, including links to foundations that provide bail funds.

y and terror, hope and fear, love and anger, humor and horror, joy and grief. I see the best and worst of humanity, and both dread and relish what could lie ahead.

My ulterior motive in writing Mindful Ethnography was to share some of the lessons I have learned about life in general and academia in particular, by working through my own health crises and an extended healing process. (See my previous blog.) I wrote it with my younger, anxiety-filled, angst-ridden school-girl self in mind, filling it with reassurances for young scholars entering this business, and calls to let go, as best we can, of our fears, worries, plans, hopes and expectations. We are being forced to let go of many plans right now.

My ulterior motive in writing Mindful Ethnography was to share some of the lessons I have learned about life in general and academia in particular, by working through my own health crises and an extended healing process. (See my previous blog.) I wrote it with my younger, anxiety-filled, angst-ridden school-girl self in mind, filling it with reassurances for young scholars entering this business, and calls to let go, as best we can, of our fears, worries, plans, hopes and expectations. We are being forced to let go of many plans right now. This is not a time to go about business as usual. My heart goes out to the many doctoral students who cannot pursue the projects they have planned for some time – like my own protégé, Sophia Angeles, who was poised to begin her dissertation research this spring, doing participant observation in a Los Angeles high school, to explore the experiences of undocumented, “unaccompanied minor” adolescent youth. Gaining access to this population will be much more challenging now.

This is not a time to go about business as usual. My heart goes out to the many doctoral students who cannot pursue the projects they have planned for some time – like my own protégé, Sophia Angeles, who was poised to begin her dissertation research this spring, doing participant observation in a Los Angeles high school, to explore the experiences of undocumented, “unaccompanied minor” adolescent youth. Gaining access to this population will be much more challenging now. At some point you may be ready to turn your mind in some new directions. And there are very new, important questions that are emerging. Identify the ways this global pandemic impacts the questions you had planned to explore, or were already exploring. For example, in Sophia’s case: How are unaccompanied minor adolescents in the U.S. being affected by COV19 in particular ways? How does the pandemic influence their social, emotional, health and well being, as well as their ideas about possible futures? What access do they have to health care, and how are their families and communities being impacted? And how are they making sense of this experience?

At some point you may be ready to turn your mind in some new directions. And there are very new, important questions that are emerging. Identify the ways this global pandemic impacts the questions you had planned to explore, or were already exploring. For example, in Sophia’s case: How are unaccompanied minor adolescents in the U.S. being affected by COV19 in particular ways? How does the pandemic influence their social, emotional, health and well being, as well as their ideas about possible futures? What access do they have to health care, and how are their families and communities being impacted? And how are they making sense of this experience? losses in our immediate and long-term futures. It may take time, even beyond the immediate crisis, to process and heal; and new crises may be looming. Both individually and collectively we will likely experience many emotions. Allow for it all, and don’t try to rush to resolution. Slowing down and really feeling whatever comes up for us can be the best thing to do during times of tremendous uncertainty. Just trust that if we ride the waves, we will get to a clearer place where we will be able to really appreciate the lessons that are there to be learned.

losses in our immediate and long-term futures. It may take time, even beyond the immediate crisis, to process and heal; and new crises may be looming. Both individually and collectively we will likely experience many emotions. Allow for it all, and don’t try to rush to resolution. Slowing down and really feeling whatever comes up for us can be the best thing to do during times of tremendous uncertainty. Just trust that if we ride the waves, we will get to a clearer place where we will be able to really appreciate the lessons that are there to be learned. this to raise fears, only to see as clearly as we can what is in front of us, so we can make more conscious choices, as the CoVID19 is helping us to do now.

this to raise fears, only to see as clearly as we can what is in front of us, so we can make more conscious choices, as the CoVID19 is helping us to do now.

On this pre-Thanksgiving travel day, I am riding a train from Copenhagen to Amsterdam – opting for ground travel rather than a much shorter plane ride, as my small contribution to reducing my overly large carbon footprint. I love traveling this way: seeing the land stretch out before me, mingling with locals, hearing the sounds of multiple languages, feeling the distances between points that are eclipsed in the air. Plus train travel offers undistracted time for reflection and writing.

On this pre-Thanksgiving travel day, I am riding a train from Copenhagen to Amsterdam – opting for ground travel rather than a much shorter plane ride, as my small contribution to reducing my overly large carbon footprint. I love traveling this way: seeing the land stretch out before me, mingling with locals, hearing the sounds of multiple languages, feeling the distances between points that are eclipsed in the air. Plus train travel offers undistracted time for reflection and writing.

I don’t think I’m brave or enlightened enough to set myself on fire. I’m not sure I’ll ever be courageous enough to voluntarily “check out” of life. And while I believe deeply in the equitable sharing of resources – not just a political stance, but one that was strongly enculturated by growing up in a family of ten people – I also recognize that even in an ideal world all resources can never be distributed with complete equity. We can strive to make things fair for others, but in the end, we each get what we get, of both tangibles and intangibles, such as our share of beauty, intelligence, love, belonging, and connection.

I don’t think I’m brave or enlightened enough to set myself on fire. I’m not sure I’ll ever be courageous enough to voluntarily “check out” of life. And while I believe deeply in the equitable sharing of resources – not just a political stance, but one that was strongly enculturated by growing up in a family of ten people – I also recognize that even in an ideal world all resources can never be distributed with complete equity. We can strive to make things fair for others, but in the end, we each get what we get, of both tangibles and intangibles, such as our share of beauty, intelligence, love, belonging, and connection.

The facilities were tucked in a far corner of this desert town, itself already well isolated from the larger metropolitan area of Los Angeles. A sign bears the GEO label; this “Modified Community Correctional Facility” is actually a complex of facilities, including a prison and two migration detention center buildings, all run by the GEO group, a for-profit management company that claims it is “committed to providing leading, evidence-based rehabilitation programs to individuals while in-custody and post-release into the community.”

The facilities were tucked in a far corner of this desert town, itself already well isolated from the larger metropolitan area of Los Angeles. A sign bears the GEO label; this “Modified Community Correctional Facility” is actually a complex of facilities, including a prison and two migration detention center buildings, all run by the GEO group, a for-profit management company that claims it is “committed to providing leading, evidence-based rehabilitation programs to individuals while in-custody and post-release into the community.” We walked into the reception area. A framed poster behind the front desk read, “General Library” and sported an image of neatly organized books. To the right of the desk was a notice for “Attorney Appointments” with a phone number. There were two bank-teller-like machines across from the desk with a potted fern in between. These machines boasted “Send money the fast, easy, reliable way.” Other signs on the walls included one that dec

We walked into the reception area. A framed poster behind the front desk read, “General Library” and sported an image of neatly organized books. To the right of the desk was a notice for “Attorney Appointments” with a phone number. There were two bank-teller-like machines across from the desk with a potted fern in between. These machines boasted “Send money the fast, easy, reliable way.” Other signs on the walls included one that dec lared, “Keep Detention Safe” and proclaimed “zero tolerance” for sexual abuse and assault. The waiting area off to the side was lined with blue plastic chairs, and sported another series of framed posters: pristine images from around the facilities, all eerily devoid of people.

lared, “Keep Detention Safe” and proclaimed “zero tolerance” for sexual abuse and assault. The waiting area off to the side was lined with blue plastic chairs, and sported another series of framed posters: pristine images from around the facilities, all eerily devoid of people.

I had thought my choices were to continue to walk the world as Marjorie Elaine Orellana (my legal name) or to file for an official reversion to my “maiden” name (Marjorie Elaine Faulstich), returning me as the person I once was: the sixth child and third daughter of Anna Marie Walter and Charles Nicholas Faulstich. But this left me feeling tugged between two poles of patriarchy that no longer served my life. I’m not sure I would know how to re-become Margie Faulstich. Nor would I necessarily want to.

I had thought my choices were to continue to walk the world as Marjorie Elaine Orellana (my legal name) or to file for an official reversion to my “maiden” name (Marjorie Elaine Faulstich), returning me as the person I once was: the sixth child and third daughter of Anna Marie Walter and Charles Nicholas Faulstich. But this left me feeling tugged between two poles of patriarchy that no longer served my life. I’m not sure I would know how to re-become Margie Faulstich. Nor would I necessarily want to. person who ever called me Marjorie Elaine. Choosing to be Marjorie E. Laine is about connecting with my father, in my own unique way, and with my self: a version of myself that holds some continuity with the past, while offering a fresh way to move into the future. (Though I must admit, there is a part of me that is declaring: “Fuck the patriarchy” – something little Margie Faulstich would never have dared say.)

person who ever called me Marjorie Elaine. Choosing to be Marjorie E. Laine is about connecting with my father, in my own unique way, and with my self: a version of myself that holds some continuity with the past, while offering a fresh way to move into the future. (Though I must admit, there is a part of me that is declaring: “Fuck the patriarchy” – something little Margie Faulstich would never have dared say.) I walked the line in ’89. I was a teacher in Los Angeles Unified School District when the teachers’ union (UTLA) led the last teachers’ strike. Thirty years later, I see things from a somewhat different angle. I’m happy to report one big difference between 1989 and now: LA teachers asked for – and won – much more than a modest and well-deserved pay raise for themselves. They advocated loudly and clearly for the rights of children and families in a public education system that has been severely eroded over the years since I left the classroom.

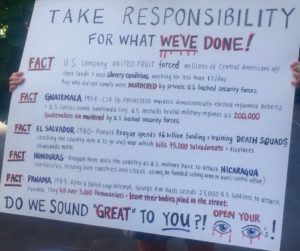

I walked the line in ’89. I was a teacher in Los Angeles Unified School District when the teachers’ union (UTLA) led the last teachers’ strike. Thirty years later, I see things from a somewhat different angle. I’m happy to report one big difference between 1989 and now: LA teachers asked for – and won – much more than a modest and well-deserved pay raise for themselves. They advocated loudly and clearly for the rights of children and families in a public education system that has been severely eroded over the years since I left the classroom. nd, and whether you believe in laws of kharma and the spiritual interconnectedness of life on this planet or not, there is plenty of evidence that the “crises” we see today were initiated long ago by actions that our country took. And the actions we take today will have profound effects on the future.

nd, and whether you believe in laws of kharma and the spiritual interconnectedness of life on this planet or not, there is plenty of evidence that the “crises” we see today were initiated long ago by actions that our country took. And the actions we take today will have profound effects on the future. ional sovereignty, borders, and the rule of law. They are achieved militarily – i.e. through violence.

ional sovereignty, borders, and the rule of law. They are achieved militarily – i.e. through violence.

Sogyal Rinpoche’s interpretation and elaboration of The Tibetan Book of the Dead (in The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying) offers a refreshingly different perspective on life and death than the dominant “denial” that permeates modern western culture. Rinpoche suggests how “hollow and futile life can be, when it’s founded on a false belief in continuity and permanence” (p. 17). He describes the way most people live: “Hypnotized by the thrill of building, we have raised the houses of our lives on sand. This world can seem marvelously convincing until death collapses the illusion and evicts us from our hiding place” (p. 16).

Sogyal Rinpoche’s interpretation and elaboration of The Tibetan Book of the Dead (in The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying) offers a refreshingly different perspective on life and death than the dominant “denial” that permeates modern western culture. Rinpoche suggests how “hollow and futile life can be, when it’s founded on a false belief in continuity and permanence” (p. 17). He describes the way most people live: “Hypnotized by the thrill of building, we have raised the houses of our lives on sand. This world can seem marvelously convincing until death collapses the illusion and evicts us from our hiding place” (p. 16).

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,

as a brotherhood and a sisterhood,